High Court affirms that under Section 46(1) Contracts Act Cap 284, where time is of the essence and a party fails to perform, the contract becomes voidable at the option of the promisee.

- Waboga David

- Aug 16, 2025

- 6 min read

High Court Affirms: Where Contracts Expressly Fix a Deadline, Non-Compliance Renders the Agreement Voidable under the Contracts Act.

Introduction

In Uganda, parties commonly enter into contracts to formalize transactions, allocate rights and obligations, and manage risks. Under the Contracts Act, Cap 284, a valid contract requires offer, acceptance, consideration, intention to create legal relations, and capacity to contract. Parties may expressly fix deadlines or performance schedules, and failure to comply with these obligations can render the contract voidable or give rise to remedies such as rescission, damages, or interest.

A fundamental principle in contract law is that only parties to a contract can be sued for breach. An agent or intermediary, such as a law firm holding funds in escrow, does not automatically assume liability for the acts of the principal unless there is evidence of fraud, bad faith, or acting outside the scope of authority.

The contract's Act stipulates that agents performing their duties within the scope of authority cannot be held personally liable for the principal’s obligations. This principle protects fiduciaries and ensures that funds entrusted in escrow are handled without imposing unintended legal exposure.

The law also recognizes the doctrine of frustration under Section 65 of the Contracts Act, which may excuse non-performance when unforeseen events make contractual obligations impossible to perform.

In Uganda, as under common law, frustration occurs when an external event, beyond the control of the parties, renders performance impossible or radically different from what was originally contemplated. Courts, however, scrutinize such claims strictly.

For example, reliance on pandemics or other widespread crises does not automatically excuse non-performance. The party invoking frustration must demonstrate that the event directly prevented performance and that no alternative means of fulfilling the contractual obligations existed. Mere inconvenience, increased cost, or delay does not constitute frustration.

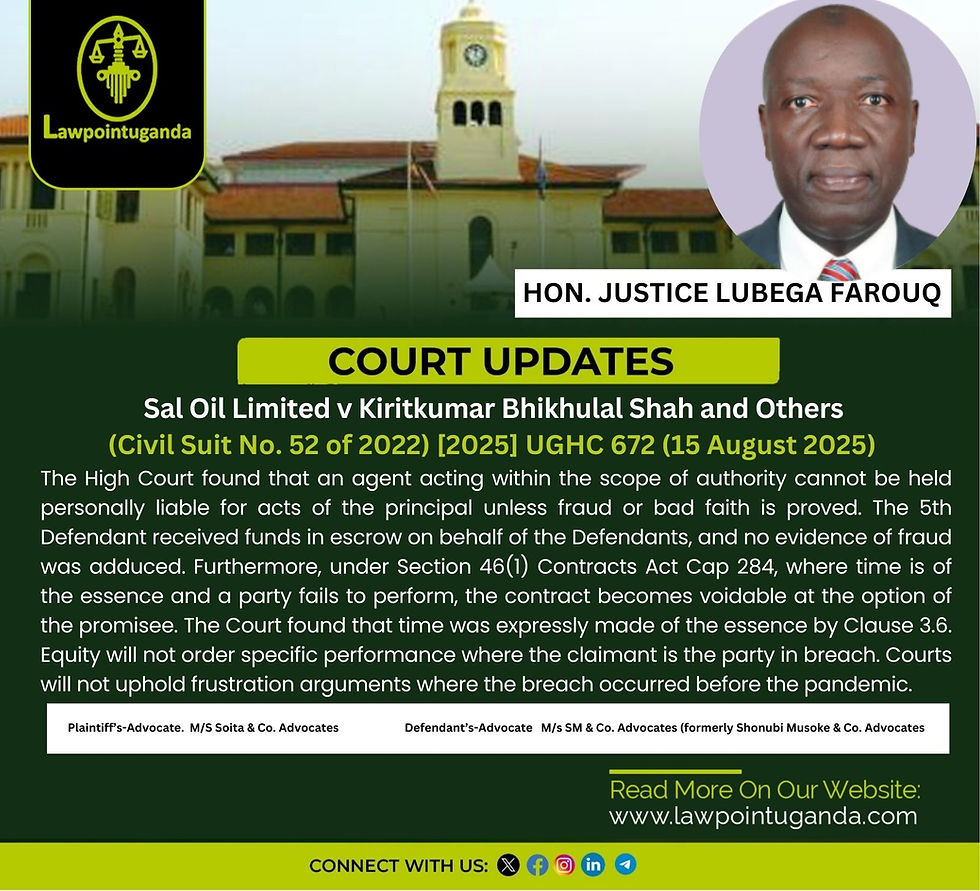

In the present case of Sal Oil Limited v Kiritkumar Bhikhulal Shah and Others (Civil Suit No. 52 of 2022) [2025] UGHC 672 (15 August 2025), the dispute involved a sale agreement for land, where the Defendants failed to deliver transfer forms.

The Court had to consider whether the Plaintiff was justified in rescinding the agreement, whether the Defendants’ reliance on COVID-19 constituted a valid excuse under the doctrine of frustration, and whether the law firm holding funds in escrow could be personally liable for the Defendants’ breach.

Facts of the Case

Sal Oil Limited (the Plaintiff) entered into a land sale agreement with the Defendants on 12th September 2019 for property comprised in Leasehold Register Volume 428 Folio 14, Plots 33 and 35 Pallisa Road, Mbale, measuring 0.416 acres.

The Plaintiff was the purchaser.

The 1st–4th Defendants were vendors, represented by the 5th Defendant (a law firm – Shonubi, Musoke & Co. Advocates) under powers of attorney.

Under Clause 3.2, the Plaintiff paid an initial instalment of UGX 100,000,000 into the 5th Defendant’s escrow account.

Disputes arose when the Defendants failed to deliver key documents required under Clause 3.6 of the contract, including resealed letters of administration, repossession certificates, caveat withdrawals, and the certificate of title, within the agreed one-month period.

The Plaintiff rescinded the agreement in September 2021 and demanded a refund of the UGX 100,000,000. The Defendants resisted, alleging performance was delayed by COVID-19 restrictions and parliamentary inquiries (COSASE). They counterclaimed for specific performance and balance of the purchase price.

Issues for Determination

Whether the 5th Defendant (law firm/agent) was a proper party to the suit.

Whether the Defendants were in breach of the agreement.

Whether the Plaintiff was in breach.

Whether the Plaintiff was entitled to rescind the agreement.

Remedies available to the parties.

Submissions of the Parties

Plaintiff

The Plaintiff argued that the Defendants materially breached the agreement by failing to provide the necessary documents for transfer, thereby justifying rescission.

The Plaintiff contended that the 5th Defendant, who managed the funds in escrow, was directly involved in the transaction and was a proper party to the suit.

The Plaintiff rejected the Defendants’ counterclaim, asserting that the conditions for specific performance had not been met.

Defendants

The Defendants contended that the 5th Defendant acted solely as an agent, and liability lay with the principals (1st to 4th Defendants).

They relied on Section 158 of the Contracts Act and case law, including Friendship Container Manufacturer Ltd v. Mitchell Cotts (K) Ltd (2001) 2 EA 338, to argue that an agent acting with the knowledge of the Plaintiff cannot be held personally liable.

The Defendants further argued that the COVID-19 pandemic frustrated their ability to travel to Uganda and complete the resealing of probate documents.

Consideration of Court

1. Liability of the 5th Defendant (Law Firm/Agent)

The Court considered whether the 5th Defendant, who acted as the law firm holding the payment in escrow, could be held liable alongside the principals (Defendants). It concluded that the 5th Defendant acted merely as an agent and did not have independent obligations under the contract.

The Court emphasized the principle that:

“An agent acting within the scope of authority cannot be held personally liable for acts of the principal unless fraud or bad faith is proved. The 5th Defendant received funds in escrow on behalf of the Defendants, and no evidence of fraud or dishonesty was adduced against them.”

The Court noted that escrow arrangements are designed precisely to protect funds while ensuring the agent does not assume liability for the principal’s contractual obligations.

Consequently, the 5th Defendant was struck out as a party to the suit.

Takeaway: Lawyers or agents holding funds in trust or escrow are generally insulated from liability unless there is evidence of misconduct, fraud, or bad faith.

2. Breach of Agreement by the Defendants

The Defendants were found to have failed to comply with Clause 3.6 of the purchase agreement, which required them to provide all completion documents necessary for transfer of ownership.

While the Defendants argued that COVID-19 disrupted their ability to travel and complete formalities, the Court held that:

“The Defendants’ reliance on the COVID-19 pandemic as a blanket excuse cannot override clear contractual obligations. The delays in resealing probate and availing documents amounted to a breach of the sale agreement.”

The Court also noted that the Defendants’ failure was substantial and affected the essence of the contract, justifying the Plaintiff’s decision to rescind.

The Court observed that:

"Section 47 now revised as Section 46 of the Contracts Act Cap 284 provides that a contract, or any part thereof, which has not been performed becomes voidable at the option of the promisee if it was the intention of the parties that time would be of the essence. Furthermore, Section 53 of the same Act allows the party for whom the contract is voidable to rescind it. According to the way Clause 3.6 of PEXH.2 was drafted, it is obvious that time was of the essence, and that is why the Plaintiff emphasized it in all its correspondences. This is also evident from the Defendants when DW1 said that he wanted to hand over the documents he had in his possession after the agreed time frame and the Plaintiff rejected them."

The Court relied on authority, citing Steedman v. Drinkle & Another [1914–15] ALL ER 298, and Sharif Osman v. Hajji Haruna Mulangwa, SCCA No. 38 of 1995,

where it was held that:

"The principle at common law and in equity is that, in the absence of a contrary intention, time is essential even though it has not been expressly made so by the parties. Performance must be completed upon the precise date specified; otherwise, an action lies for breach… However, in equity, time is essential if the parties expressly stipulate that it shall be so."

Takeaway: A global or national crisis may not automatically excuse non-performance; courts will assess whether the breach goes to the fundamental obligations of the contract.

3. Breach by the Plaintiff

The Defendants contended that the Plaintiff had breached the agreement by refusing to accept certain documents and by rescinding the contract.

The Court rejected this claim, reasoning that the Plaintiff had acted within its contractual rights, given the persistent non-performance by the Defendants. The Court stated:

“The Plaintiff’s rescission was not premature but rather a contractual right triggered by the Defendants’ continuing failure to perform. The Plaintiff was under no obligation to accept partial or incomplete performance.”

This confirmed that the Plaintiff’s rescission was lawful and did not constitute a breach.

Takeaway: A purchaser may lawfully rescind a contract when the vendor fails to perform essential obligations, particularly after repeated attempts to compel performance.

4. Entitlement to Rescind

On the issue of rescission, the Court confirmed that the Plaintiff was entitled to terminate the contract and demand a refund. The decision was guided by the principle that:

“Where one party materially breaches a contract, the aggrieved party may rescind the agreement and recover any payments made, including associated interest if stipulated.”

The Plaintiff had followed proper procedure, including formal notice to the Defendants, and the breach was sufficiently serious to justify rescission.

Takeaway: Material breaches entitle the non-breaching party to rescind and recover payments, including interest if contractually agreed.

5. Remedies

In light of the findings, the Court awarded the following remedies to the Plaintiff:

Refund of UGX 100,000,000/= – the first instalment paid under the agreement.

Interest at 24% per annum from the date of breach until full repayment.

Costs of the suit.

The Court dismissed the Defendants’ counterclaim for specific performance and damages, holding that:

“Specific performance is not available to a party in breach. Given the Defendants’ failure to perform essential obligations, they cannot compel the Plaintiff to complete the transaction.”

Takeaway: Courts will enforce rescission and interest rights strictly, and counterclaims for specific performance will fail where the claimant is itself in fundamental breach.

Read the full case below

.jpg)

Comments